“Wabi-Sabi”

The term wabi-sabi, like the labels “natural” or “mindful,” gets a lot of use these days. In its most reductive sense, wabi-sabi is a Japanese aesthetic philosophy of imperfection. There’s an undeniable comfort to seeing a human touch on objects in a moment marked by an excess of glossy and over-designed images. But what differentiates wabi-sabi from incompletion at its mildest, or sloppy resignation at its worst?

Wabi-sabi relates to the design principle of mono no aware and the larger Buddhist framework of valuing transience, impermanence, and fallibility. Wabi-sabi can refer to simplicity, asymmetry, austerity, closeness. It’s the tap of a finger on a just-thrown bowl in order to gently disorient the perfect, centrifugal circularity of a piece. Beauty is not antithetical to wabi-sabi— pursuit of perfection is. A Greek vase or a Keats’ sonnet do not express wabi-sabi, but a tea bowl by Bernard Leach or a poem by Ezra Pound might.

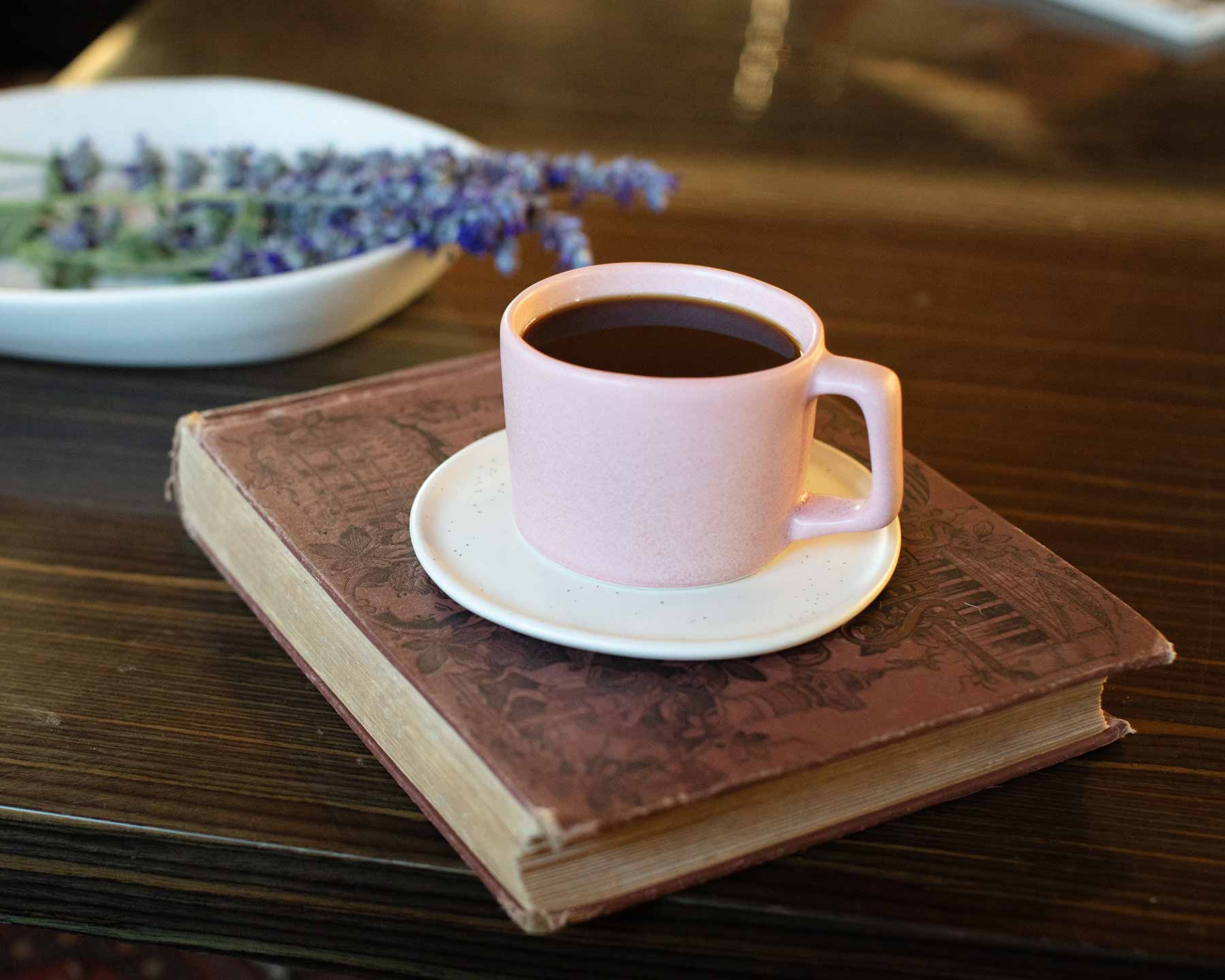

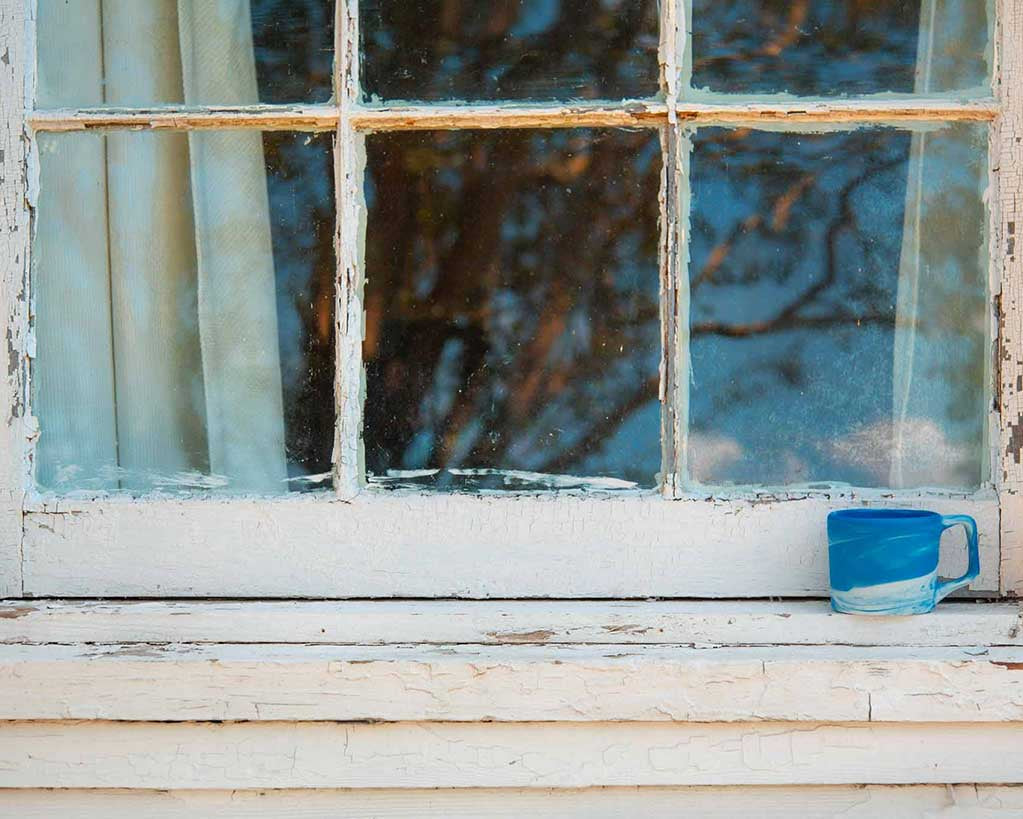

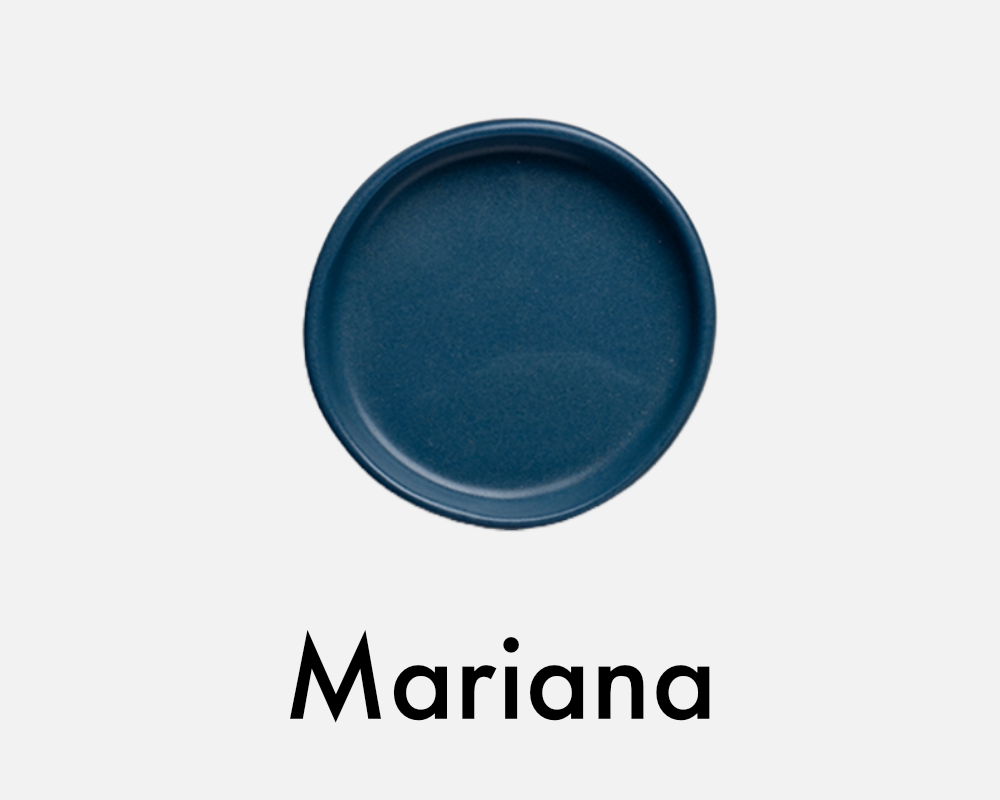

Haand’s interpretation of a notably difficult-to-pin-down principle— see Marcel Theroux’s 2009 BBC Four series “In Search of Wabi Sabi” for a gentle mockery of the Western anxiety to define the term— depends on the very handmade-ness of our wares. Rather than seek to produce perfect copies of our designs, Haand values the human touch that informs every part of our process. Variations in glaze, slight discrepancies in shape, and other marks of crafting create communication between the owner and the maker of a Haand piece. In handling and using a piece made by Haand, a customer can see the craft behind the piece as well as its design.

-Casey Ireland, January 2021